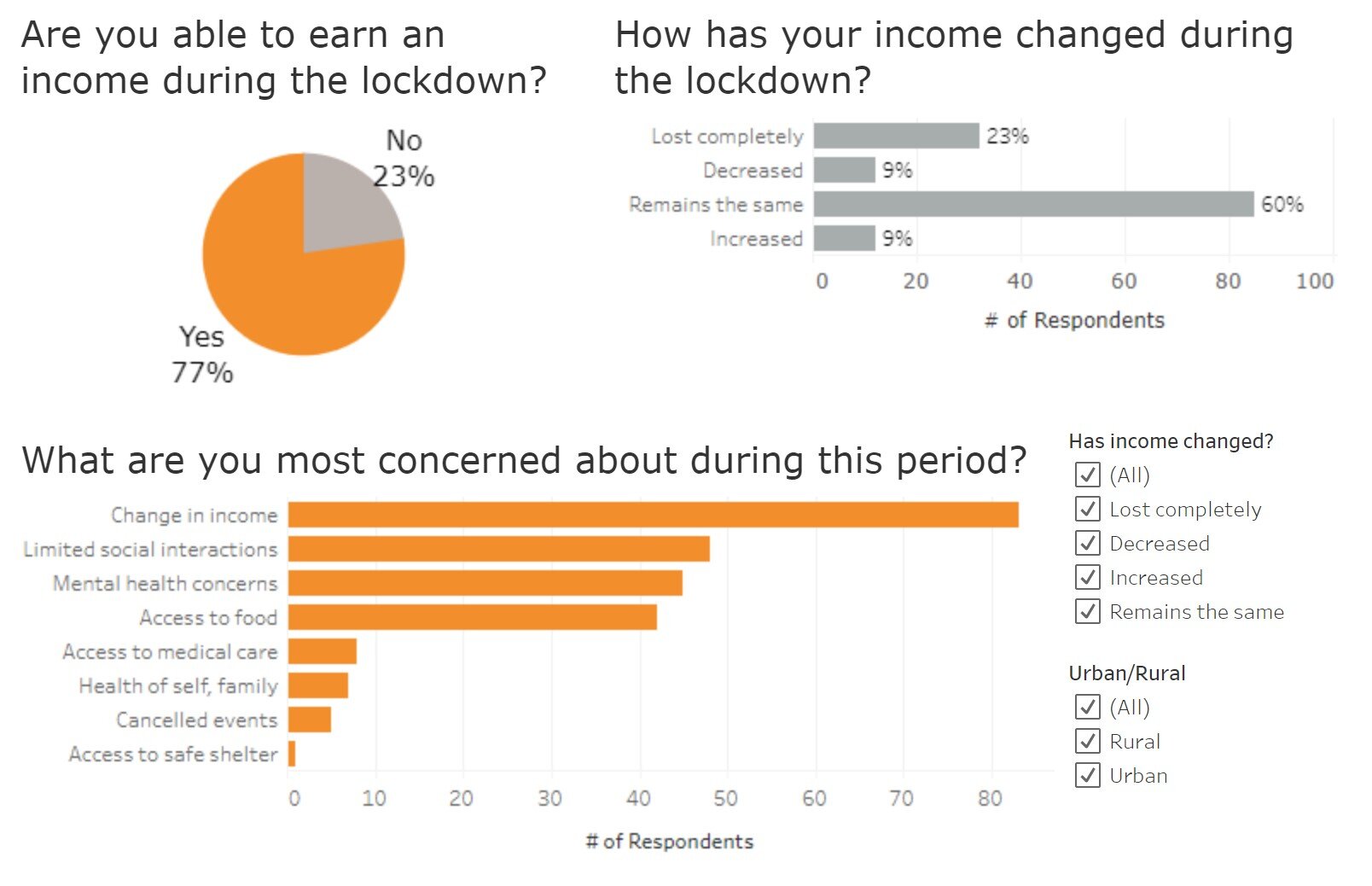

When India’s nationwide lockdown came into force on March 24th, 2020, the immediate and worst impact of this decision was felt by vulnerable populations such as migrant laborers and low-income citizens. At Upaya, we build a ladder out of extreme poverty for these vulnerable communities, so we wanted to understand how, and to what extent, COVID-19 and the resulting lockdown had impacted their lives, directly from them.

In a few short weeks, we conducted phone surveys with 141 jobholders from six partner companies and shared our survey findings on our blog. Company-specific analysis has been shared with each partner as well, to help inform their decision making during this unprecedented time. We continue to collect surveys, and will update our dashboard as responses come in.

UPAYA’S SURVEY APPROACH

At the start of 2020, we had planned to survey several hundred jobholders to assess their progress out of poverty. We routinely conduct baseline surveys with jobholders employed by all of our new partner companies. We also conduct midline surveys after two years have passed. With these surveys, we collect data from jobholders on their income and savings, household assets and livestock, housing condition, meal consumption, and job satisfaction.

We partner with an enumerating agency to conduct all of these surveys in-person, which we find valuable to ensure the accuracy of survey responses and create a personable survey environment for respondents.

A CHANGE IN COURSE

With the pandemic, our standard surveys were suddenly not possible, nor were they appropriate. We de-prioritized our standard surveys but we still felt that it was necessary to check in on jobholders. In re-designing our surveys to a phone survey format, we coordinated the whole process virtually, while navigating the limited bandwidth of our partner companies.

At a time when many organizations are reimagining how their work is done, we thought we would share our key lessons from this process for those interested in collecting feedback from stakeholders during this unusual time.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS

1) Assess whether your standard practices are appropriate or relevant

With the lockdown coming into force and uncertainty around its duration, we realized it was not possible to conduct our regular baseline and midline surveys. Not only could we not do them in-person, but we also did not feel comfortable conducting them at all for several reasons:

The regular survey, where we ask about income and household affairs, might be insensitive in the current context, where jobs and incomes may be severely impacted.

Our standard baseline surveys only make sense when we are studying variables occurring during a normal business cycle. Even for those who have kept their jobs, the lockdown was anything but normal. In the absence of that, we felt that the probability of accurate data collection would have been low.

Most business operations had come to a halt with the lockdown, which has a direct impact on livelihoods. In conversations with our partners, we understood the impact of the situation might be felt in different ways – financially, health-wise, socially, mentally, and otherwise. We wanted to specifically understand all these dimensions further and directly from the jobholders.

We felt the insights from the Covid-19 survey would be useful for our partners to take appropriate action, where needed, to support their jobholders in this situation.

2) Adapt your methods to suit the current situation

Conducting surveys during the lockdown meant that we couldn’t do the surveys in-person as we usually do. We had to move quickly, and the next best alternative was to switch to phone surveys. Luckily, our enumerating agency is experienced in phone surveys and helped us design the new survey.

Some important activities will support a logistical switch:

Choose the right survey tool: It’s important to use a tool that has been tested previously by your organization and is easy to deploy. We rely on having a tool that has both online and offline functionalities. We used the KoBoToolbox platform, which our enumerators were also experienced with. This is not a time to test new platforms, as you are likely stepping into action quickly and without usual time to prepare.

Brainstorm potential challenges and mitigants: Since this was our first time conducting phone surveys, and given the situation, we talked through possible challenges around logistics and coordination, availability, and sensitivities of jobholders and data collection. For example, how many times should we attempt to call a jobholder? What time in the day would be least intrusive? What questions would help us verify their identity?

These questions helped us make decisions on the survey flow in terms of building a rapport, softer opening questions, taking jobholder consent up-front, and responding appropriately based on the tone. Our enumerators also had to listen to verbal cues that would signal a respondent wanted to wrap up the survey.Map out process and logistics: We established a detailed timeline for the overall outline, process, and expectations for the survey. This included the end-to-end process from designing and deploying the surveys, coordination with partners, data sharing, and defining clear roles between Upaya and the enumerators. Given the sheer number of calls and coordination that had to take place in a compressed timeframe, it helped to have partner surveys run sequentially, but with clear and manageable call schedules for each.

3) Be clear, specific on what your main objectives are and design the survey to match

We designed new survey questions based three key objectives:

Understand how the COVID-19 situation and lockdown has impacted lives of those vulnerable to extreme poverty

Understand how they have been supporting themselves financially, and what additional support is required

Share data with our partner companies so that they could take action where needed

The objectives then drove our survey design and deployment in the following ways:

Brief length: It was challenging, but we forced ourselves to keep the survey short – a maximum of 11 questions, which took an average of 10 - 15 minutes per survey. We designed it as such keeping in mind the stress these jobholders were under and their time constraints. This time limit also forced us to focus only on those questions that are relevant to the outcomes we set out to achieve.

Open ended questions: Given the uncertainty of the situation, we wanted to ask more open ended and qualitative questions. The intent was to explore and understand the impact of the pandemic on jobholder lives and not be restricted by specific categories (i.e., multiple choice questions) which would have been created based on our assumptions.

Though this approach made analysis more challenging as we had to manually categorize responses, it did result in a rich diversity of responses that provided insight into what jobholders were actually experiencing.Ensuring sensitivity in the current context: We did not know how and to what extent the pandemic and the lockdown had impacted jobholder lives. We wanted to approach them with questions that were respectful and not invasive. We found it critical to get feedback on survey questions to ensure we weren’t asking questions that could potentially be insensitive or inappropriate or trigger negative emotions. The survey was shared with our partner entrepreneurs and enumerators beforehand and modifications were made based on their feedback.

Since the enumerators wouldn’t be on the ground to see and understand the local dynamics, we shared with them the current context based on what we heard from our partners. For example, some communities had been hit harder by food shortages than others, and we wanted to be careful when asking how the household was managing these challenges. This helped the enumerators understand the sensitivities – especially given that the situation varied from state to state – and how jobholders needed to be approached while conducting the surveys.

4) Secure buy-in from key stakeholders early on

This was a crucial aspect in the process. Most operations were at a standstill and companies were in survival mode. The surveys were optional, but when we set the context and outcomes, most of our partner entrepreneurs were keen to participate to better understand how their jobholders were affected. This helped us get their support in the implementation process.

From Upaya’s perspective, we tried to minimize the entrepreneur’s bandwidth towards this process, except for sharing contact information and gaining permission from jobholders.

5) Stay on top of the data coming in

While surveys were being conducted, it was important to us to get regular updates from the enumerators. Using our data collection tool, we were also able to keep track of and view responses as they came in. While most of the process was smooth, keeping an eye on responses helped us troubleshoot any challenges quickly, before the problem affected an entire sample. For example, we observed that one particular question was being misinterpreted in a particular state, perhaps due to the local dialect. Other logistical challenges that arose included accessibility due to network issues in remote areas, varying availability of jobholders, multiple attempts to reach several jobholders, and rushed interviews in some cases.

The surveys for each company spanned over two to three days on average but were spread out over the course of about four weeks to accommodate schedules and the bandwidth of our partner companies.

LOOKING AHEAD

All in all, although it was difficult to gauge over the phone, there was a sense that jobholders appreciated having an opportunity to share their concerns, and that our partner companies appreciated the feedback they received. All of these findings will be valuable inputs as our partner companies plan for the road to recovery.

Contributors: Rachna Chandrashekhar, Sachi Shenoy, and Daphne Delaski